“The less biodiverse any system is, the greater the potential for its collapse.” Janisse Ray, from The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food.

“The less biodiverse any system is, the greater the potential for its collapse.” Janisse Ray, from The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food.

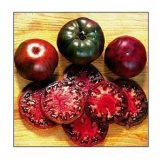

We’ve been reading headlines stating that 93% of seed varieties available in the early 20th century had disappeared from commerce by 1980. The biggest factor in this drastic decline in diversity is consolidation of the industry. The big multi-national corporations have systematically bought up smaller companies and in so doing have ended production of vast numbers of time-tested open-pollinated and older hybrid varieties and prioritized the production of new patented proprietary hybrids.

The corporate model is: eliminate anything that is not a big seller or appeals to a limited market sector or is best suited to specific geographic or climate needs like drought or heat-tolerance. The remaining varieties are ones best suited to industrial-scale production systems, sacrificing quality in favor of quantity, and to geographic areas with ‘ideal’ growing conditions (like California). In other words, exactly the opposite of what we need in order to be prepared for the impending extreme climate events and changes. In The Organic Seed Grower, author John Navazio notes that “few new vegetable crop varieties are adapted to a wide array of conditions.”

This trend has also proceeded without concern for our health. For example, Dr. William Davis, author of Wheatbelly, points out “Modern industrially-bred wheat has been associated with a steep rise in gluten intolerance and with structural changes in wheat protein that lead to obesity and many other diseases”.

This trend has also proceeded without concern for our health. For example, Dr. William Davis, author of Wheatbelly, points out “Modern industrially-bred wheat has been associated with a steep rise in gluten intolerance and with structural changes in wheat protein that lead to obesity and many other diseases”.

A move in a positive direction came recently when Mexico’s Supreme Court ruled that no GMO corn will be allowed to be planted in Mexico. In 2001, researchers showed that GMO corn had contaminated native corn varieties. Corn (aka maize) is the national heritage of Mexico, the place where corn originated and where at least 59 landraces of locally-adapted traditional varieties still persist.

Fortunately, for several decades, there has been a grass-roots movement afoot to save and bring older widely adapted edible varieties back to commerce, and to select, reselect and breed varieties that don’t sacrifice flavor, nutrient-density, and affordability in favor of shelf-life, ease of shipping and mechanized planting and harvest. Beyond the vegetable and fruit garden, a new recognition of the importance of beneficial insects, pollinators and urban/suburban wildlife habitat has led to an increase in the availability of seed for plants that support and build ecosystems.

Fortunately, for several decades, there has been a grass-roots movement afoot to save and bring older widely adapted edible varieties back to commerce, and to select, reselect and breed varieties that don’t sacrifice flavor, nutrient-density, and affordability in favor of shelf-life, ease of shipping and mechanized planting and harvest. Beyond the vegetable and fruit garden, a new recognition of the importance of beneficial insects, pollinators and urban/suburban wildlife habitat has led to an increase in the availability of seed for plants that support and build ecosystems.

The pandemic has affected seed companies in a big way. With much increased demand, shortages of labor and materials at seed-growing farms, and transport delays, seed shortages have been an issue. Climate change and extreme weather events have taken their toll as well.

At Harlequin’s Gardens, we not only sell seeds, but also grow an enormous number of our plants from seed. Some of the seeds we use are collected from our own gardens, a small portion are collected by permit from local public wildlands, but the majority are purchased from seed purveyors. These purveyors are buying seed from growers around the world. Your typical seed purveyor is purchasing seeds from a handful of big multi-national corporations.

At Harlequin’s Gardens, we not only sell seeds, but also grow an enormous number of our plants from seed. Some of the seeds we use are collected from our own gardens, a small portion are collected by permit from local public wildlands, but the majority are purchased from seed purveyors. These purveyors are buying seed from growers around the world. Your typical seed purveyor is purchasing seeds from a handful of big multi-national corporations.

We (Eve and Gary) do all we can to buy from the seed companies that grow their own or and/or support small-scale, organic seed-producers, innovative USA breeders from the public and private sectors, work to preserve open-pollinated heirloom varieties, and bring forth varieties that will succeed and excel in our changing climatic conditions.